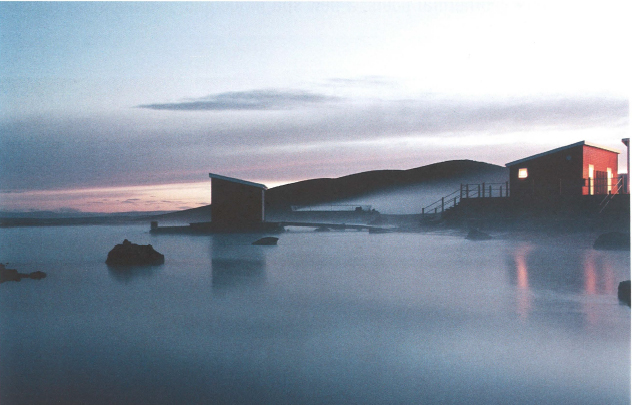

Fed by boiling geothermal pools, a new spa in Iceland combines environmental sensitivity and jaw-dropping views.

By Katherine E. Nelson; Photos by Brian Sweeney

Originally published in Metropolis magazine

NOTE FROM KATHERINE: This is one of my all-time favorite pieces of journalism involving a crazy trip to the tippy top of Iceland. It was off-season, freezing and wonderful…

“What do you do if you’re lost in an Icelandic forest?” architect Halldor Gislason asks. We’re driving along a desolate stretch of highway in Iceland’s remote northeast, headed for his latest project, the Myvatn Nature Baths, a natural spa. As the car sails past majestic fjords blanketed by scrubby brush, brilliant red berries, and green and mustard-colored moss, Gislason smiles and delivers the punch line: “You stand up!”

There are very few trees in Iceland. Most of the countryside is barren arctic desert, where storms of black volcanic sand can kick up in an instant. The remote Myvatn region epitomizes much of the country’s fearsome beauty with its looming volcanic craters, sulfur-streaked hillsides, and boiling geothermal pools. For hundreds of years farmers have eked out a living on this cold and distant piece of earth. Silica mining and fishing along the country’s northern coast also contribute to the local economy. But with declining fish populations all across the North Atlantic and the closing of a nearby silica plant, natives have been forced to look to new industries, including tourism, to sustain their community.

In 1998 a group of 30 entrepreneurs joined forces to fund the Myvatn Nature Baths, a spa complex that taps a long tradition of natural steam bathing in the area. Home to volcanoes and all matter of geothermal activity, the region already attracts more than 100,000 birdwatchers, nature buffs, and scientists a year to view the wonderfully strange, seemingly unspoiled surroundings (a huge number when you consider that the entire population of Iceland is less than 300,000). The purpose of the baths was to offer these visitors “some extra experience in conjunction with hiking around the area,” says Gislason, who anticipates that the new attraction will also extend the condensed tourist season-which peaks during the long sun-filled days of July and August-to provide year-round employment for local workers.

In Iceland there is a recent precedent for the nature baths-the Blue Lagoon, a man-made pool of mineral-rich water that opened in 1999 in the country’s more densely populated southwest. The milk-white bath sits in the middle of a sprawling black lava field, and its success rests on providing bathers with an intimate experience of Iceland’s extreme natural environment. Both the Blue Lagoon and the Myvatn Nature Baths are the only bathing pools in Iceland created from the pure runoff of a geothermal power station.

But before Gislason could break ground at the nature baths, he faced several hurdles. To preserve the unique local environment, the Icelandic government formed a special Myvatn-Laxa conservation area in 1974; a national committee of scientists and environmentalists oversees development there. In addition to the strict environmental regulations, the living, breathing landscape, with its active volcanoes and mercurial fumaroles, adds an element of unpredictability to the work of even the most prepared architect. For example, during construction a steam fissure opened in the middle of the Myvatn lagoon, causing a major change to the design.

After several years of lobbying the national committee, the key to finally obtaining approval for the development came from Gislason’s astute choice of building site. Shunning several untouched locations near Lake Myvatn, the dramatic central feature of the landscape, Gislason instead placed the nature baths back from the shoreline in an environmentally damaged area that contained a massive gravel-mining pit, which was then remediated and landscaped to create the lagoon. “What helped us get approval was that we worked toward tidying up the area and making it more environmentally friendly,” Gislason says. In fact, the new development helps to regulate the flow of people through the area, which should curtail further environmental damage. “We are closing off a lot of tracks-and the possibility for people to drive all over the place in their pickup trucks,” he says.

Because the site sits back from the lake, visitors make their approach by winding through the ancient Jardbadshlar, or “Earth Bath Hills,” along an unpaved road behind the development. Descending down into the nature baths, the view suddenly opens into a panorama of the entire region with the lake stretched across a horizon punctuated by half-domed craters. While the view may be out of this world, the architecture itself is notably down to earth. “Making a very prominent building would have been another way to do this,” Gislason says. “But there wasn’t the money or technology. So why try as a designer to do something that isn’t going to work?”

Instead of building one massive central edifice, he designed the architecture to showcase the views and to cause the least amount of visual and environmental disruption. His plan entails a complex of low buildings that snuggle together in clusters around the central lagoon. Each building serves a different purpose, from saunas to changing rooms. In the lagoon’s center one solitary steam bathhouse, which visitors can reach by a short footbridge, becomes the focal point for the design. The visual vocabulary of this central building-a modest brown hut with a white door, white roof, and white window-repeats itself in each of the buildings with only slight variations. Each roofline tilts at a slightly different angle, creating a playful dialogue with the different volcanic peaks surrounding the lagoon. Due to the limited budget as well as the volatile environment, the complex is extremely flexible, and buildings will be added over time.

Gislason took his inspiration for the low-tech buildings from the simple, inexpensive storage sheds-built by farmers just after World War II that litter the Icelandic countryside. “If I built a hut like that in the middle of Reykjavik, I don’t think people would think it was very nice,” says Gislason, who claims that the central bathhouse “isn’t a beautiful object until you place it in the middle of the lagoon. Most buildings built today in Reykjavik look like they could be in Amsterdam or Los Angeles. The architecture is not International Style—it is Icelandic vernacular.”

In addition to his work on the nature baths, Gislason currently heads the Department of Design and Architecture at the new Iceland Academy of the Arts, the country’s first university-level design institution. Like many Icelandic architects, Gislason received his training abroad-he studied architecture at the University of Portsmouth and in 1980 took semiology courses in Italy with Umberto Eco. A longtime advocate for design in Iceland, he spent nearly a decade spearheading plans for the new department, which finally opened in 2001. Only recently, with the launch of the school as well as the increased profile of Iceland’s international tourist image, has a homegrown awareness of design finally taken root. “We are such a small community,” Gislason says. “A big corporation could actually buy Iceland. So how do you work on your identity and try to reinforce something here? You need to improve education and make people more aware of design.”

As for the ultimate impact of the Myvatn Nature Baths, Gislason hopes that they will be instrumental in improving the local economy while preserving the landscape. The development implements strict regulations for new land use, but even more important may be Gisalson’s own contribution toward the creation of a new wave of Icelandic architecture. Since the majority of Icelandic architects have studied abroad, it has been traditionally popular to look to the United States and Europe for inspiration. With the new development, Gislason (who claims he “is just as guilty as everyone else” in “stealing ideas from abroad”) may inspire his fellow Icelandic architects to rediscover their own architectural past. “I’m hoping that this project is not about me,” he says. “And for me that is a new kind of an attitude.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.